A new scientific framework offers potential for personalized health and wellbeing care.

In this world of disruption and change, the demands on all of us are higher than ever, yet we’re often not handling our demands with high levels of wellbeing and growth. Instead of thriving, we often function from a state of chronic dysregulation.

We pay a high personal cost for operating this way. Over time, our chronic stress can develop into a host of physical, mental, and social health challenges, such as high blood pressure, migraines, sleep disturbances, digestive issues, depression, anxiety, breakdowns in relationships, and diminished meaning and performance in our lives and work.

Our organizations and societies pay a high cost, too. Currently, 60% of employees in major global economies feel overstressed, with hybrid workers and women frequently reporting the highest stress levels. Nearly half of millennials worldwide report concerns about their long-term financial future, and 1 in 5 adults report feeling lonely. In Wisdom Works’ research, we find managers with lower levels of wellbeing generally linked to lower levels of impact.

So, I was delighted to talk with Dr. Rachel Gilgoff about a new scientific framework for understanding the biology of stress that she and her colleagues are putting into practice. Rachel is Chief Medical Officer at the first-of-its-kind California Institute for Stress & Resilience. Watch our conversation below.

She’s also a trauma and integrative specialist with over ten years of experience as a board-certified general pediatrician and child abuse pediatrician, plus part of Wisdom Works’ growing community of wellbeing and leadership development professionals, we call Be Well Lead Well Pulse® Certified Guides, advancing leadership for thriving and stress resilience in organizations around the world.

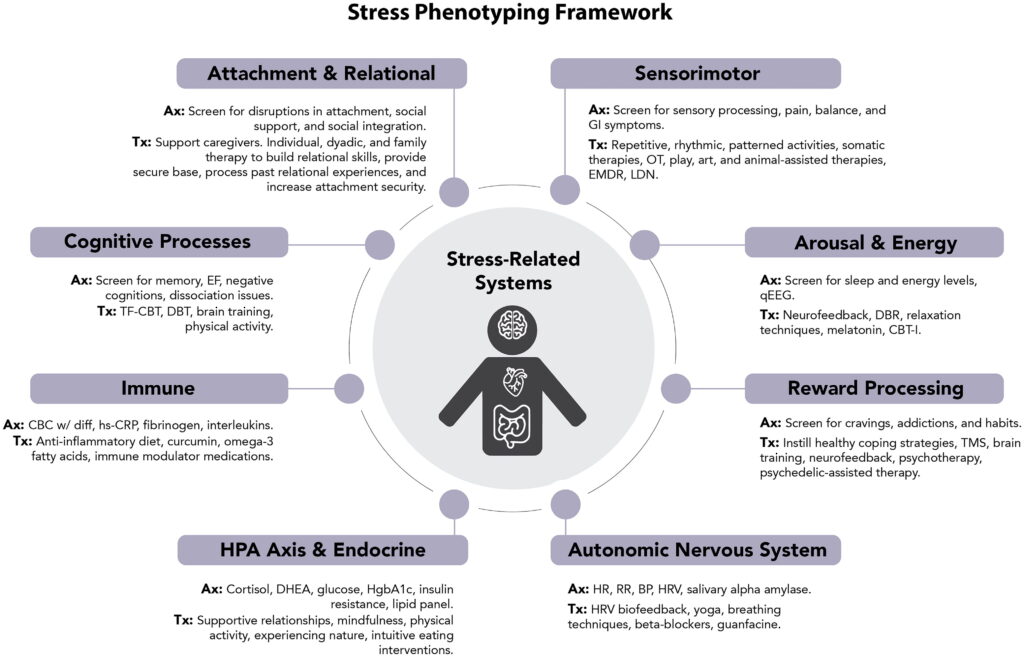

During our conversation, Rachel shared the new stress phenotyping framework, a mental model designed to help us understand how our experiences can affect our individual physiology. The framework outlines eight mechanistic pathways for chronic stress and evidence-based approaches for treating stress based on each pathway.

I find this framework particularly exciting not only because of its integrative nature, but also because of its potential to target and personalize health and wellness care.

Gilgoff, R. et al. (2024) ‘The Stress Phenotyping Framework: A multidisciplinary biobehavioral approach for assessing and therapeutically targeting maladaptive stress physiology’, Stress, 27(1). doi: 10.1080/10253890.2024.2327333.

Rachel and I also discussed how the evolutionary purpose of our stress response is to help us survive, how we may pass our traumas from generation to generation, and in today’s environment, how being bombarded with stressors (such as digital overload) may be training us to live and work from a reactive orientation.

I disclosed a significant trauma to Rachel that occurred many years ago. At that time, my stress response went on overdrive, expressing as itchy skin from head to toe, hypervigilance, a bone-deep fatigue, and along with a host of other symptoms, the diagnosis of interstitial cystitis, a horrible chronic bladder pain condition. (Fortunately, a dear friend encouraged me not to identify with that IC diagnosis, and after many years of intentional healing, I became symptom free—today, some of the same symptoms I experienced then start cropping up like an early warning system that lets me know I’m getting too stressed.) Based on the stress phenotyping framework, Rachel gave me a completely new insight about how my physiology had been working for me during that intensely stressful time, rather than against me.

Towards the end of our conversation, Rachel and I explored the relationship between stress and authentic thriving. We also examined the profound shifts necessary for leaders, healthcare, and all organizational systems if they want to truly lead wellbeing.